Introduction#

A comparison between research projects conducted two decades ago and those of today reveals a marked increase in the demands placed upon early career researchers (ECRs; Weissgerber, 2021). This can be attributed, in part, to factors such as the need for larger sample sizes (Fan et al., 2014; Marx, 2013; Zook et al., 2017), the incorporation of novel methods such as pre-registration or dissemination (Ross-Hellauer et al., 2020; Tripathy et al., 2017), as well as the growing utilization of advanced computational and statistical techniques (e.g., machine learning; Bolt et al., 2021; Bzdok & Yeo, 2017) and cutting-edge technologies such as virtual reality (Matthews, 2018). All of these factors contribute to an increased time commitment required to successfully undertake such research endeavors (Powell, 2016). Accordingly, the motivation and eagerness many ECRs feel during their first years is more and more often accompanied by feelings of being overwhelmed (Kismihók et al., 2022; Levecque et al., 2017), as many project choices have to be made and a variety of skills need to be learned quickly that determine the long-term success of one’s first research project.

At this stage, however, most ECRs lack the necessary expertise and experience to make such important decisions. Moreover, learning the ‘language of science’ can be difficult (Parsons et al., 2022; see also Table 1). In addition, institutions and supervisors often provide researchers with a relatively fixed array of conventionally used resources, such as subscription-based or in-house software. These tools are often expensive and/or bound to the institution itself (i.e., may become unavailable when the researcher changes institutions). These limitations in resources might not only impede, but also prevent good scientific practice. Although many open access tools have been proposed to facilitate project work, these resources are often spread out and hard to compare with each other in terms of reliability, validity, usability, and practicality (but see a collection of open science-related resources from the Framework for Open and Reproducible Research Training spanning multiple fields). Taken together, dealing with these difficulties may be time-consuming and create a (potentially error-prone) resource-labyrinth, further exacerbating the uncertainty of how, and with which tools, high-quality science can be conducted.

The Resource#

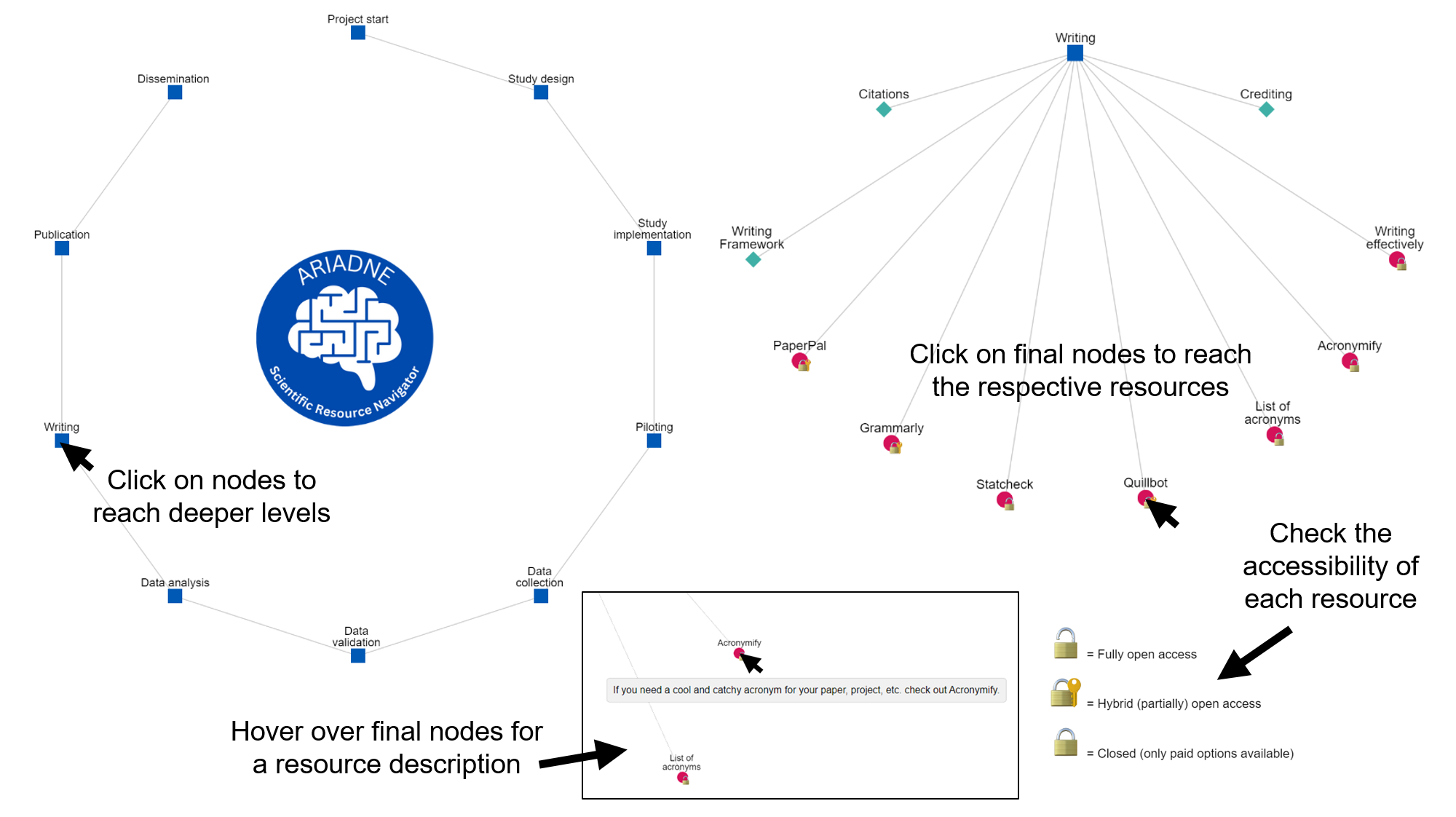

ARIADNE. Therefore, a comprehensive overview of curated resources is warranted. ARIADNE is a living (e.g., continuously updated with new contributions from the research community) resource navigator that helps to search a dynamically updated database of resources (see also Figure 1 and exemplary resources marked with ➜ in the subsequent text). We named our tool ARIADNE, as we aim to help researchers navigate the ‘labyrinth’ of research tools and resources, much like the mythological Ariadne helped Theseus navigate the labyrinth (see e.g. here. Our tool is available as a dynamic interface for easier use and searchability and was developed by researchers in the fields of biological psychology and neuroscience, with wider applications to all fields of psychological science. The open-access database covers a constantly growing list of resources that are useful for each step of a research project, ranging from the planning and designing of the study, over the collection and analysis of the data, to the writing and disseminating of the findings. We include a broad range of tools, but put a specific emphasis on open and reproducible science practices, as these practices become more and more valued and even mandatory in many fields of psychological science (Kent et al., 2022).

Technical specifications. Detailed usage instructions and the corresponding source code are freely available online. The tool is divided into two sections: a web-hosted Jupyter Book detailing the aforementioned steps and a Cytoscape network showcasing the steps dynamically and interactively. We selected this framework due to the robust capabilities offered by GitHub for project management, development, and deployment within a single platform. Additionally, GitHub Pages can host tools generated via JavaScript backend. We have exploited this feature to develop our network tool using a Cytoscape.js (Franz et al., 2016) backend. Furthermore, we have secured the backend by locally hosting the Cytoscape.js instance within our project’s GitHub repository. This approach safeguards the project from potential disruptions caused by significant changes in the Cytoscape.js backend, as we maintain our own copy of the Cytoscape.js instance.

Collaboration opportunities. There are multiple ways to contribute to the database and tool. First, users can directly submit new resources to be added via a Google Form or a GitHub issue, as this technique has proven useful for earlier versions of this tool (see e.g., here). As we have expected that not all future users are well-versed with GitHub, each submitted Google Form will automatically create a unique issue in the GitHub repository. Once the issue is submitted, the ARIADNE Team will review the entries (e.g., regarding functionality of links and compatibility with the tool’s framework) and, upon approval, integrate them into the relevant subsection. Similarly, software bugs and other issues can be reported directly through GitHub or Google Forms to allow for version tracking. Therefore, we characterize our tool as a community-driven and open-source tool.

Long-term sustainability. Many community driven projects suffer, when core members driving the initial effort turn to other projects or leave science altogether. We have therefore put special emphasis on the sustainability of ARIADNE. ARIADNE is supported institutionally by the Leibniz Institute for Psychology (ZPID), which is a research institute with long-term funding from the renowned Leibniz Gemeinschaft for infrastructures to support psychological science in Europe. ARIADNE was initiated by and is sustained by the Interest Group for Open and Reproducible Science (IGOR) of the section Biological Psychology and Neuropsychology, which forms part of the German Psychological Society (DGPs), and currently consists of 100+ members conducting active projects (e.g., Nebe et al. 2023). ARIADNE is thus embedded in institutional and community structures of psychology in Germany, which will aid with long-term availability and scaling plans going forward. In the future, we hope to attract support also from international partners championing open science initiatives.

The tutorial. In the following tutorial, we will guide researchers through a standard research project in psychological science, facilitated by ARIADNE. We divide the research cycle into 10 steps that determine the quality and the success of research projects. We describe the challenges and choices to be made in each step and provide curated resources from ARIADNE for each of them: 1) project start, 2) study design, 3) study implementation, 4) piloting, 5) data collection, 6) data validation, 7) data analysis, 8) writing, 9) publication, and 10) dissemination. We also introduce key terms relevant in each step to facilitate training and communication between experienced and new academics (see Table 1 and italicized words in the main text). Lastly, we provide a checklist with questions one might ask at each step of a research project in Table 2. Please keep in mind that some of these questions may be relevant before starting a certain step.

Figure 1. Exemplary visualization of ARIADNE - the scientific resource navigator. Clicking on nodes leads to deeper levels (black arrow keys), with the final level showing all associated resources including descriptions and hyperlinked websites (e.g., Project sStart → Literature → 10 ways to Open Access). Lock icons indicate the accessibility of a certain resource.

Figure 1. Exemplary visualization of ARIADNE - the scientific resource navigator. Clicking on nodes leads to deeper levels (black arrow keys), with the final level showing all associated resources including descriptions and hyperlinked websites (e.g., Project sStart → Literature → 10 ways to Open Access). Lock icons indicate the accessibility of a certain resource.